Mechanical keyboards are all the rage right now, especially for PC gamers. But the trend has been going for over a decade at this point, and there are only so many LEDs you can stick inside a plastic case before consumers ache for something new. That new hotness is adjustable actuation, a technological leap forward in the way keyboards work. And unlike some of the more nebulous features of high-end keyboards, this has tangible benefits in terms of what they can actually do.

That said, it’s also pretty complicated, and the benefits offered by adjustable actuation are so niche that many users might not even notice them. Let’s demystify this new tech, so you can decide if it’s worth the considerable premium over a standard keyboard.

Further reading: The best gaming keyboards

What is key actuation?

In terms of keyboards and mechanical switches, actuation just means the point at which a switch registers an input. So for example, you rest you finger on the A key, but it doesn’t immediately type “A” into your computer. You have to press down a little before the key registers. That point at which the key sends the input into your computer is the actuation point.

In a modern mechanical switch based on the Cherry MX standard (which is now out of patent, and in use by the majority of keyboard and switch makers), a switch registers its actuation by closing an electrical circuit. When you press down on the key it depresses a plastic stem that in turn compresses a spring. When the stem goes low enough, it allows two metal contacts to touch. When the metal touches, the circuit closes, and the keyboard sends the corresponding command to the computer. When you take your finger off the key the spring pushes the stem back up, and the metal contact points separate again. This is the “mechanical” action in the mechanical keyboard moniker.

Check out this short video from Cherry to get a visual on how this works:

There are two important variables here that I’d like to highlight. The spring inside the switch comes in different strengths — the stiffer the spring, the harder you have to press down to register a keypress. This is expressed as a measure of force, either in grams of weight compressing it or in centiNewtons (cN) of straight force. Mechanical keyboard fans generally just shorten this to “Newtons” as a quick way of expressing how stiff or strong the switch is, and how “hard” you have to type to use the keyboard. The Cherry MX Red switch actuates with 45 centiNewtons of force.

The other factor is more relevant for this discussion: the actuation distance. That’s the distance between the switch’s resting state with no pressure on it, and the point at which the metal leaves connect and register a key press. For the Cherry MX Red switch in the video above, it’s 2.0 millimeters. You can keep pressing the switch after it actuates for another 2mm, for a total distance of 4mm before the stem hits the plastic housing of the switch and “bottoms out.” But pressing down beyond the actuation point doesn’t actually do anything else, since the circuit is closed and won’t be open until you release the key.

2mm and 4mm don’t sound like much. But there’s a lot of variation in switch designs, and those tiny distances are shockingly noticeable to your fingers. For example, most laptop keys travel for 1mm or less, 1.5mm if it’s a high-quality design. Those milimeters can make the difference between a keyboard that feels snappy and responsive and one that feels like a weight training session just to type out an email.

Further reading: Best gaming keyboards

What is adjustable actuation?

Adjustable actuation is pretty much exactly what it sounds like: It’s the ability of the key switch to adjust the point at which it actuates. In simpler and more practical terms, the keyboard lets you set how hard or light you need to press on the keys before they register. Some keyboards can activate with as little as 0.1mm of travel — just one-twentieth the distance of the Cherry MX Red switch above — all the way down to a 4mm bottom-out actuation.

On this SteelSeries keyboard, the alphanumeric key area (white) has magnetic switches with adjustable actuation, while the rest are normal MX-style linear switches (red).

Michael Crider/Foundry

That means that you can choose whether your keyboard is on a hair trigger, so to speak, or needs a complete depression of the key in order to register, and anywhere in between. This is particularly desirable for gamers, who want a light touch, or typists who have a very particular taste when it comes to actuation.

One thing to keep in mind: This adjustable actuation is digital, not physical. The keyboard is detecting how far down on the spring the stem depresses, but the spring itself doesn’t change — it can’t. You’re changing the actuation distance, not the actuation force. So a key that requires, say, 55 Newtons of force in order to completely depress will still feel just as “stiff,” even if it only now requires 25 Newtons to depress the switch to the actuation point.

How do adjustable actuation switches work?

Now we’re getting into some really technical stuff. Because standard MX-style mechanical switches are fairly simple, at least in a purely electronic sense, they need a lot of design work in order to get to the point where you can set the actuation point yourself. In fact, some designers and some keyboard fans don’t even consider adjustable actuation switches to be “true” mechanical switches, although they seem very similar from the outside.

But that’s semantics. There are two primary ways in which current keyboards give their keys adjustable actuation: optical and magnetic.

Optical switches

In a standard mechanical key switch, the actuation occurs when two points of metal touch each other. An optical key switch replaces this physical interaction with a beam of light. Optical switches have been used in electronics for a long time, and they’re also relatively simple: You have a beam of light emitted at point A and detected at point B. Move something between them, and the beam of light is broken. Point B no longer detects the light, and so the switch activates — or de-activates, depending on how you set it up.

These simple on/off switches are also used in some optical-mechanical keyboards. Press down the key, the beam is interrupted, and a key press registers. The advantage is that without those metal parts touching each other, the switch feels “smoother” and less janky. But you can take it a step further by making the optical sensor more complex. These complex sensors don’t just detect whether or not the beam of light is interrupted, but how much light is being blocked.

Think of it as standing in a dark bedroom with a light on in the hall. When you crack the door a little bit, a sliver of light enters the room. When you open the door halfway, you get a bit more light. When you open it fully, you can see most of the room. That door opening and letting the light through is how an adjustable actuation optical switch detects a key press: The more light is blocked by the stem pressing down and interrupting the beam, the harder you’re pressing on the switch.

Here’s a video from Razer that shows how a standard optical switch (on/off) works (0:55), and how an “analog” version with adjustable actuation detects more or less light (1:30).

Magnetic switches

A beam of light isn’t the only way to achieve this effect. You can also stick some magnets in the switch instead. This sounds complicated (how do they work, et. al.), but it really isn’t. There’s a magnet on the bottom of the stem, and a sensor on the bottom of the switch (or even outside of it on the circuit board).

As the stem depresses in the switch, the magnet gets closer to the sensor, and the keyboard measures the magnetic force between them. The closer the magnet, the stronger the force, and the further down the actuation is detected. At no point do the magnet and the sensor touch.

This setup is sometimes called a “Hall effect,” named after some very fancy physics and also used in some anti-drifting thumbsticks that don’t need components to rub against each other. But for the purposes of keyboards, the end result is that the keyboard detects how far away the stem is from the sensor, and uses software to choose where it actuates. Here’s a promotional video from SteelSeries showing these magnetic switches in action (0:26).

What can an adjustable actuation keyboard do?

As I’ve already explained, the biggest draw of an adjustable actuation keyboard is that it lets the user set the key actuation distance, from as little as 0.1mm (a “hair trigger”) to the full bottom of the sensor, usually around 4mm. But there are some other tricks these fancy switches can do that might be less obvious.

‘Analog’ sensing

Because an optical or magnetic switch can detect how far down the stem is being depressed, it can translate that motion into an analog input. Like a joystick or a thumbstick on a controller that detects how far or “hard” you’re pressing in one direction, a switch in analog mode can be set up to transmit how soft or hard you’re pressing it. It isn’t truly analog input, but with 40 or so different positions on the switch in just a few millimeters of travel, it’s pretty darn close.

Michael Crider/Foundry

This has some limited applications, but it’s undeniably useful in games. The most popular use is setting up the usual W, A, S, and D keys (forward, left, down, back) to correspond to a joystick input. While it can’t do the same kind of 360-degree motion as a true joystick, you can carefully adjust your pressure on each key to simulate it. A standard keyboard that works like a joystick — pretty cool!

Rapid trigger

Rapid trigger is a feature that truly “twitch” gamers can appreciate. In its standard mode, an adjusted actuation key will register that you’ve released the key at a specific point. Say you’ve set the actuation point at 1mm, but you’ve pressed the key all the way down to its 4mm bottom-out maximum. The key won’t register that you’ve released it until the spring pushes the stem all the way back up, past the 1mm point.

With the rapid trigger software feature activated, an adjustable actuation key will “release” its input at any point when it detects less pressure. So if you’ve gone past your 1mm actuation point down to 4mm, it can release the key the millisecond you ease up the pressure, and the switch raises to the 3.9mm point. Rapid trigger settings can adjust these values to be more or less sensitive.

What’s the point? Generally it’s great for incredibly touchy movement in fast-paced first-person games. Keyboards are already preferred for this kind of thing, since it takes less time to alternate between the A and D keys with your index and ring finger than it does to rock a thumbstick from one side to another. If you’ve seen a “pro” or esports gamer move their character left to right and back with eye-blurring speed, they might have been using the rapid trigger function to go even faster.

Double actuation

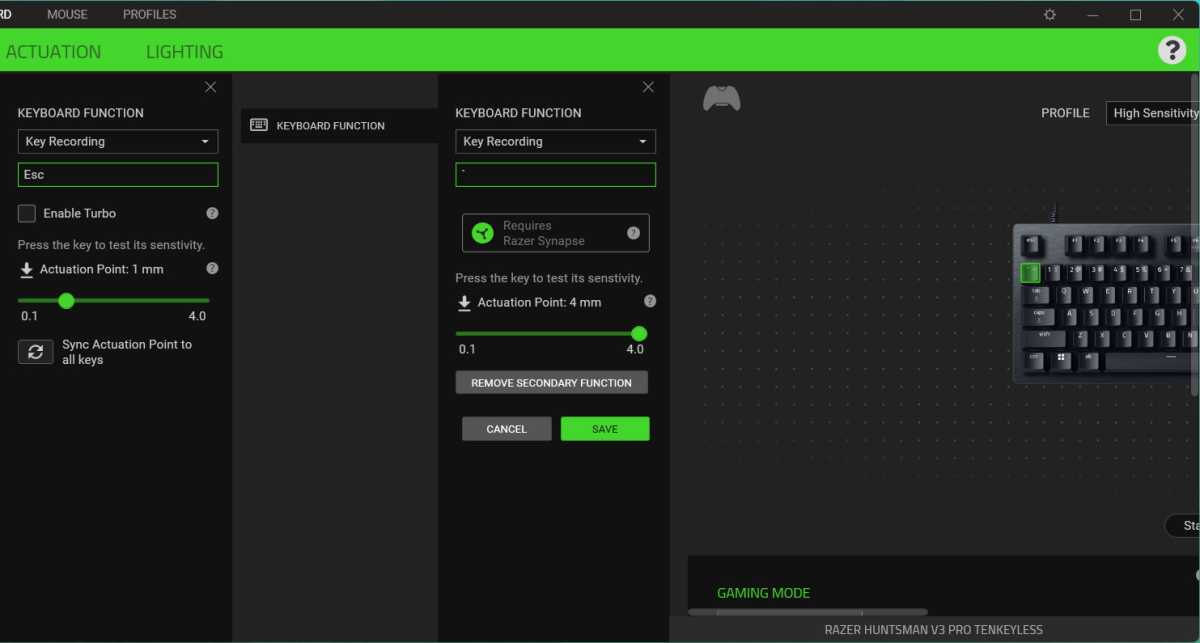

Double or dual actuation is somewhat self-explanatory: setting two functions to just one key. Usually a keyboard needs a modifier key (like Shift or Fn) in order to switch between layers and activate multiple functions. But because and adjustable actuation keyboard can sense how deeply you’re pressing each key, it can do it all in one.

Take the back tick or grave accent key (`), for example. (It’s the one above Tab.) Because it’s so close to the Escape key, some more compact keyboards combine them, making you press a function key to activate the back tick (Fn+Escape = `). But on an adjustable actuation keyboard, you can set both of these to the same key — press down a little to pass the first actuation point at 1mm for Escape, press down harder to reach the 3mm secondary actuation point and type a `.

Michael Crider/Foundry

How about a more practical example? You could set up a media key to lower the volume with a light tap, or mute it completely when the key is pressed down fully. Personally I find this functionality a bit hard to use practically. It takes a lot of setup, a bit of memorization, and some re-training of muscle memory to use effectively. But it’s a trick you just can’t pull off with a standard keyboard.

The downsides of adjustable actuation

So you’ve learned what an adjustable actuation keyboard can do. What about its drawbacks? The first part is pretty obvious: the price. Adjustable actuation switches are far more complex than regular mechanical switches, requiring some pretty sensitive sensors underneath each and every key. That makes them more expensive.

Take Razer’s popular keyboards for example. The BlackWidow V3 uses regular mechanical switches, fashioned in the Cherry MX standard. It’s $140 right now. The Hunstman V3 Pro, which uses optical switches with adjustable actuation, is $250. Are those fancy capabilities above really worth $100+ more? That’s for you to decide.

The adjustable actuation switches on the Razer Huntsman make it cost over $100 more than the very similar BlackWidow.

Razer

Because of the way they function, switches with adjustable actuation can’t really have a bump or a click at the actuation point. You can’t get the gentle pressure of a Cherry MX Brown switch, or the loud click of an MX Blue switch. Adjustable actuation switches can simulate an old-fashioned mechanical keyboard by requiring a deeper press, but they also can’t have a spring that’s too stiff. So if you like your keys super-strong, you’re out of luck.

And finally, adjustable actuation keys are so complex that they generally need to be soldered in place on the keyboard’s circuit board. That means that hot-swappable switches, one of the most popular features of high-end “custom” keyboards, are out. You can adjust the software all you want, but the hardware isn’t going to change.

Michael Crider/Foundry

While it’s possible to design an adjustable actuation switch that can be swapped out, it would need to be compatible only with other adjustable actuation keys, meaning the massive selection of Cherry-style switches are still off-limits. That’s a huge bummer for anyone who wants to make their keyboard truly customized. On the plus side, custom keycaps are usually still compatible, as keyboard designers are careful to stick to cross-shaped stems.